Despite the ridiculous price spikes for used vehicles – the CPI for used vehicle retail prices spiked 41% year-over-year in February, and Manheim’s wholesale price index for used vehicles spiked by 38% – there’s no shortage of used vehicles on dealer lots. There is plenty of supply. But new vehicles have been in a historic shortage due to the semiconductor shortages and the ensuing production cuts. And this has changed how the industry operates.

The number of used vehicles on lots of franchised and independent dealers in February (purple line in the chart below) rose to 2.62 million vehicles, the highest since December 2020, according to data from Cox Automotive. This was down by 9% from the average inventory in 2019 (2.88 million vehicles).

But the number of new vehicles on dealer lots has been hovering at catastrophic lows. In February, dealer inventories edged up to 1.07 million vehicles (red line), which was down by 70% from the average in 2019of 3.66 million vehicles.

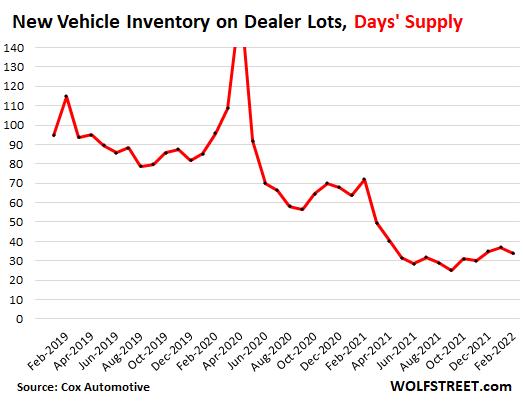

The standard metric in the retail industry of days’ supply shows how many days this inventory at the beginning of the month would last at the current rate of sales, with no additional vehicles added to inventory. The metric is a function of both, the number of vehicles in inventory and the number of vehicles sold during the prior 30 days, and it eliminates the effects of inflation on inventories.

Used vehicle supply ticked down to 51 days in February mostly due to higher sales in February than in January. This supply of 51 days is above average supply in 2019 of 48 days, and above average supply in 2021 of 41 days. In other words, there is plenty of supply, at the current rate of sales:

But new vehicle supply at dealers ticked down to 34 days. Before the pandemic, 60 days’ supply was considered healthy. The average in 2019 was 90 days, which was too high due to the slowdown in new vehicle sales at the time. During the lockdowns in March and April 2020, when sales ground to a near-halt, supply spiked. But then sales picked up again in mid-2020, and the production cuts due to the semiconductor shortages became the #1 problem:

Total combined supply of new and used vehicles and of auto parts at dealers, which the Census Bureau reported yesterday for January, declined to 1.24 months (about 37 days’ supply), having stayed in the same catastrophically low range since March 2021, with hardly any improvements.

This data from the Census Bureau goes back 30 years, to 1992, unlike the above data sets that only go back to 2019. It shows just how much of an outlier today’s vehicle inventory has been. But by combining new and used vehicles and parts, it papers over the catastrophically low levels of inventories at new vehicle dealers:

When the Federal Reserve today released the industrial production data for February, which includes manufacturing, there was another bad number for manufacturing production of motor vehicles, components, and parts. This is the sector that has been most severely hit by the semiconductor shortages and by other supply chain issues.

The index for production of motor vehicles and parts has been in the same low range since the beginning of 2021, when the semiconductor shortages started to bite. In February, production was roughly level with February 2021, but was down 11% from February 2020, and was back where it had been in 2014.

Despite the drop-off in production of motor vehicles and parts (red line), the overall index of Industrial Production ticked up to the highest since 2008 (purple line):

Production cutbacks by automakers is a global issue. Toyota just announced a series of production cuts at some plants globally. EV maker Rivian, which just started getting its pickups out the factory door, announced last week that it might have to cut production this year in half. The German automakers are now coming out with further production cuts, on top of those caused by the chip shortages, because some of their key component makers – such as of wiring harnesses – are in Ukraine and have shut down. Every day seems to produce a new challenge.

Supply chain challenges always existed, but most issues could be resolved fairly quickly. Now the issues are multi-layered and widespread, with new causes being added to it, such as the difficulties of the component suppliers in Ukraine and Russia.

As a result of the inventory shortages of new vehicles, customers have switched in large numbers to ordering vehicles and waiting patiently till it arrives.

But it’s hard to gauge actual demand for new vehicles because supply is so low. Vehicles are sold at mind-boggling prices, for mind-boggling per-vehicle gross profits at dealers and automakers, as customers are still paying whatever to get a new vehicle.

And there is enough demand at these mind-boggling prices, given the constrained supply, and inventories have not yet been building in any meaningful way. A significant inventory build would mean that supply is outrunning demand at those prices. But that hasn’t happened yet.

So right now, sales are limited by what automakers can produce. In February, only 1.05 million new vehicles were sold. This was down by 12% from February 2021 and by 22% from February 2020. These are historically low sales going back to the 1970s:

Automakers and dealers are loving the mega-record per-vehicle gross profits, and they’re loving that customers have stopped haggling and just pay whatever, including over sticker, and they’re loving the large-scale shift by customers to buy via make-to-order, rather than off the lot.

This is a system Tesla, which doesn’t have franchised dealers, implemented from get-go. Make-to-order solves all kinds of issues. It solves the problem of some units getting old sitting on the lot and having to be sold at deeply discounted prices. It solves the issues of inventories piling up and dealers being overstocked, such as in 2019, when automakers had to heap costly incentives on the market to get those vehicles over the curb.

Manufacturing vehicles that have already been sold is a more efficient way of selling, and both dealers and automakers want to encourage customers to keep doing that. And dealers would love for customers to keep paying MSRP or over MSRP.

But they all would like to sell more vehicles at those per-vehicle mega-profits. Which means that automakers will have to be able to get their supply chains straightened out and build more – but they don’t ever want to overbuild again, like they used to, because such inventory gluts cause profits to plunge.

The semiconductor shortages have upended the old way of doing business in the auto industry, and have upended how customers buy new vehicles, such as paying sticker or over sticker and ordering vehicles rather than picking one out on the lot. Retail customers could always order, but it was just a few customers who did. Now lots of customers are doing it.

The dream for the industry – but not necessarily for the customers who have to pay for this – would be if automakers and dealers can maintain this system of how customers buy, and what they pay, with dealers operating on very lean inventories and mega profits, even as production starts recovering from the shortages.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? Using ad blockers – I totally get why – but want to support the site? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.